What is social impact? How do you measure it? How do you know when you’ve made any impact in the first place? These are just a few of the millions of questions I’ve been asking over the last couple of years on my social entrepreneurship journey.

Coming into the social sector from a solidly private sector background, the frequent use of the word “impact” was something I found puzzling at first. It was uttered in nearly every conversation I had and it appeared to refer to some common understanding that only I hadn’t caught onto. But if I asked three people what it meant I would get three completely different answers. It started making sense to me as I got to spend more and more time working closely with non-profits and social enterprises getting a broader perspective of how success is measured.

Defining Social Impact

In the private sector, the guiding principle behind performance measurement is pretty simple: deliver profits predictably and increase shareholder value. These are not sufficient, however, for social enterprises and entirely irrelevant for non-profits. Success in these organizations is measured first and foremost by the effect they have on the well-being of the individuals and families in the communities they work in – in other words “social impact”.

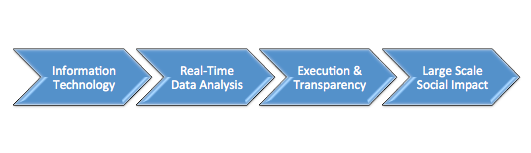

A desired impact can be defined in broad terms (e.g. “the sustained well-being of children within families and communities“) or in very specific terms (e.g. “empower and deliver affordable small-scale biogas and bio-sanitation systems to customers“). The next step is to figure out how to measure it and, more importantly, demonstrate the link between your activities and the outcome. This is often both a qualitative and quantitative activity for which many organizations utilize information technology (IT) systems of some kind.

But what about the technology? Does IT itself create social impact? We believe it does. Information technology enables social enterprises to amplify their impact by removing barriers to scale. Well implemented IT will also increase transparency, which in turn makes it easier and less costly to secure investment and funding.

I’ll use an example to help clarify the point.

IT and Social Impact: Tackling Energy Poverty in Africa

In sub-Saharan Africa, nearly 620 million people live without access to electricity (half of the world’s total), 36 million of them in Tanzania alone (source: WEO Report 2014). Solar energy, and in particular small solar lanterns have emerged as a promising and affordable solution for off-grid households. However, according to Lighting Africa (a joint IFC-World Bank program) these products have reached less than 4% of the target households as of the end of 2012. There is a demand and there is clearly a supply, so why has so little of this market been addressed?

According to the manufacturers and distributors interviewed by Lighting Africa, the two biggest barriers they face in this market are lack of access to finance and distribution challenges such as transaction costs, poor infrastructure and managing disperse and fragmented distribution networks. Thin distributor margins complicate things even further.

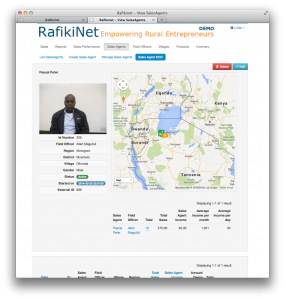

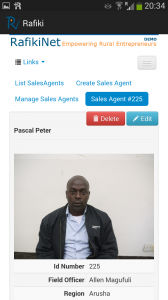

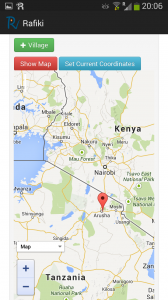

In order to reach all of those off-grid households, new and existing social enterprises must overcome these hurdles and scale further than they have been able so far. We believe that a purpose built data and mobile technology platform like RafikiNet is the first step toward achieving the scale needed to make the necessary impact.

Lowering Distribution Barriers

In a post earlier this year we described how we worked with Global Cycle Solutions (GCS) in Tanzania to address precisely these challenges. Since implementing RafikiNet, GCS has been able to scale up and reach more than 10,000 new households with solar technology. They did this through a network of more than 100 Village Level Entrepreneurs (VLEs) across Tanzania – who themselves earned a total of more than $40,000 USD in income – and all of that was in just one year.

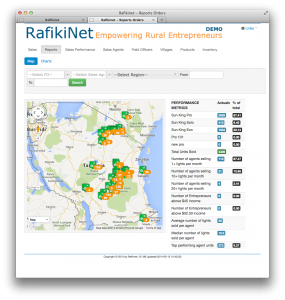

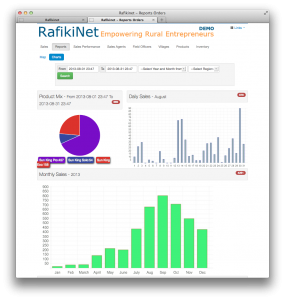

The resulting data in RafikiNet itself also proved to be very valuable as it revealed important trends in the market. The data showed us that sales surged during the months of harvest seasons in regions relying heavily on agriculture – an insight which helps distributors better forecast and better align their investments and operations with local economic cycles.

We also learned that while an average VLE can reach between 60-120 off-grid households (300-600 people) in a year, a high performer working in a well-managed micro-franchising network can reach more than double that and earn between $3-5 per day in the process – not bad in a place where the average income is just $1-2 per day.

All of this taken together, we came to a major realization:

A well managed micro-franchising network scaled successfully up to 6,000 VLEs is capable of delivering solar energy products to one half of Tanzania’s entire off-grid population within 5 years , not to mention generating millions of dollars in income for the villagers themselves in the process.

Now that is major social impact! It’s also an incredible opportunity for impact investors and social funding providers. Eliminating Financial Barriers

Eliminating Financial Barriers

By virtue of having ready access to this kind of data in the first place we also begin to addresses the other major barrier: lack of access to finance. Better transparency, up-to-date metrics, and clear evidence of social impact make it much easier for potential investors and financiers to perform due diligence and make it more likely that an organization will receive the needed funding in a timely manner.

Fostering Lasting and Large Scale Social Impact

None of this is to suggest that IT by itself can solve these problems. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the toughest environments in the world to work in and there are countless organizations – both with and without IT – making incredible impact.

What information technology does do, however, is lower the barriers to scale so that immediate local impact can become lasting global impact.